Experiment 1: Butterfly Pea Powder, Part 1

Share

Did you know that, under the right conditions, some plants can change color? The butterfly pea flower is one of those, and I've heard that it can be used to color baked goods. So, I designed an experiment to try it.

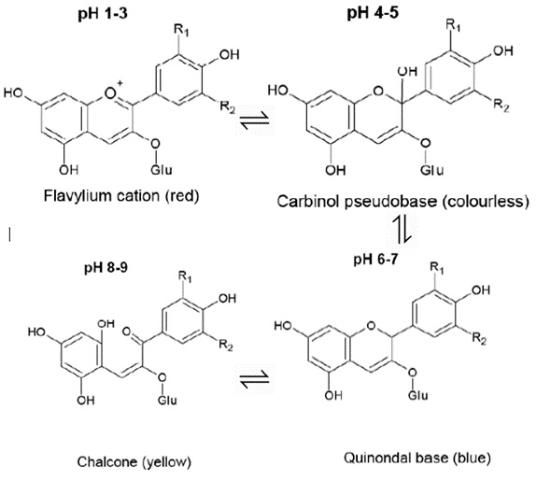

Some background: Powdered butterfly pea flowers typically have a deep blue color when mixed into drinks and baked goods. However, in acidic conditions, it changes to a nice purple. Under basic conditions, it becomes more green. This happens because of changes in the balance between the different forms of the molecule responsible for the color. In neutral conditions, there's a pretty equal balance of the red and blue forms of this molecule. When the pH is lowered and the solution becomes more acidic, that balance is pushed towards the red form, causing the color to become more purple. When the pH gets higher and the solution becomes basic, the balance shifts towards the yellow form and the color shows up more green. If you think this color-changing property is super cool and want to read more about the science, here is a very interesting article.

So, my experiments had two purposes. First, I wanted to test how well a powdered flower would color macaron shells. Second, I wanted to see the color-changing properties in action.

My macaron process always begins with getting all my ingredients prepped: separating eggs, weighing sugar, and sifting together almond flour and powdered sugar. For this batch, I knew that, in order for the color to change the way I wanted, I needed to make my batter mixture acidic, so I used a French meringue and added a pinch of cream of tartar (pH = 3.5) to my sugar.

Once I had all of my ingredients ready, I started mixing. I threw the egg whites straight into the mixer bowl, and for my experiment, I added about an eighth teaspoon of the butterfly pea powder in right away (my first mistake).

The color started out as exactly what I was expecting: a nice, deep blue. However, not all the powder was fully mixing in. It was a little clumpy, and I realized I maybe should have sifted it or at least broken up the bigger clumps before adding to the egg whites. But it was too late, so I left it to mix, hoping the clumps would dissolve as the meringue whipped.

The color started out as exactly what I was expecting: a nice, deep blue. However, not all the powder was fully mixing in. It was a little clumpy, and I realized I maybe should have sifted it or at least broken up the bigger clumps before adding to the egg whites. But it was too late, so I left it to mix, hoping the clumps would dissolve as the meringue whipped.